It’s a heritage that reaches back 2,000 years, to when American Indians dug tunnels 40 to 100 feet deep to cull mica from the ground. They valued its shiny quality for making beads and decorative belts, adorning graves, and use as money. From colonial years until the early 20th century, the locals — white settlers and Cherokees alike — mined mica and feldspar in the region. Mica was in such voluminous supply that, after the Civil War, researchers busied themselves finding things to do with it. Then, in 1879, along came Thomas Edison’s newfangled electric motor, whose wires needed the insulation provided by sheet mica. Then along came radios and other electronics that required mica components. From the 1860s until the 1960s, commercial mica mines pecked into these woods like sapsucker holes in hickory bark. As a nod to the mica boom, there’s even a community in Yancey County named Micaville.

Decades of mica mining left behind piles of flung-away feldspar, which wasn’t as commercially coveted in the late 19th century. But in 1910, these scrap heaps brought a shine to the eyes of a gem prospector from Baltimore named William Dibbell. He scrubbed them real nice and sent a shipment to a big ceramic plant in Ohio called Golding Sons. The plant bosses liked the ceramic-grade feldspar so much, they drafted a contract for him to supply Golding Sons with more and more. This allowed Dibbell to found the Carolina Minerals Company of Penland. By 1917, North Carolina was the nation’s top feldspar producer.

Until about 1949, most of the mining work, especially extracting the mineral from ore, was done by hand.

The making of a mining Mecca

Earthmovers with names like Caterpillar and Komatsu have replaced the father-and-son outfits slinging sledgehammers. Now, dozers and dynamite tear into the terrain and reshape mountains with ease. But the process of building those mountains is mind-aching to comprehend. The annals of geologic study show that the Appalachian Mountains began forming at least 480 million years ago, the product of plate tectonics. This scientific theory asserts that the continents — the plates — drifted and bumped into each other, demolition derby-style. Have two cars collide head-on, and watch their hoods crumple and heave upward. It’s the same idea with drifting landmasses, except the crumpling happens very … very … slowly.

Alex Glover, a geologist who lives in the area, says the Spruce Pine Mining District was created about 380 million years ago when Africa shoved into North America. (The Himalayas, by comparison, are only about 50 million years old.) That collision created incredible friction-fueled heat — more than 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. This was happening, he says, nine to 18 miles below the surface. The rock down there melted, forcing its way through cracks in the surrounding rock. This was rich, mineral-making liquid that cooled and crystallized over the millennia to become today’s buried treasure.

What made the Spruce Pine quartz so pristine was the lack of water where all this friction occurred. Water, Glover says, would have injected all kinds of impurities. “There is no other place that has the purity of quartz,” he says, referring to these mountains that have enthralled him for most of his 58 years. It’s why he lives here now, in a log cabin-style house on a hilltop wreathed in Fraser fir Christmas trees. He has a panorama of his beloved Blue Ridge, with his living-room window and deck saluting a wide-open view of Mount Mitchell. Today, under a cobalt sky, a pillow of clouds cushioning its uppermost reaches, Mount Mitchell looks magnificent.

Excerpt from Our State Magazine, article by Bryan Mims.

History of the NC Mineral and Gem Festival

1959-2019

The first Mineral and Gem Festival in Spruce Pine was produced by the Spruce Pine Chamber of Commerce and was called the Spruce Pine Mineral and Gem Festival. Chamber President Harold Van Day and Secretary Sudie English Stoppard decided to organize a festival to bring tourists to the area and spotlight the mining heritage of the area. The manager of the Festival was Mr. Peter Lowe . It was held August 5-7, 1959 at Harris High School.

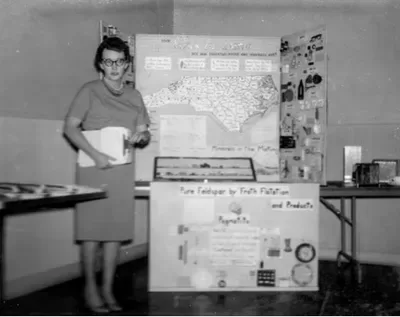

In 1961, Mrs. Charlie Mae Sproles became the director of the festival. Mrs. Sproles (pictured below) a local teacher, combined a love for mineral and gem collecting with rising interest in the hobby to organize the North Carolina Mineral and Gem Festival.

The Festival became the North Carolina Mineral and Gem Festival in 1969.

In 1984, on the Silver Anniversary of the Festival, the event moved from Harris High School to the newly completed and air-conditioned Pinebridge Coliseum which allowed the event to grow and add additional vendors.

Stay tuned for more !

Chestnut Flats Mine

By Rhonda Gunter, Mitchell County Historical Society

Initial mining in Mitchell County, in the 1880s, was for mica, dug in a few large operations but also in small family mines which brought in extra money when men were not busy farming. By the 20th century, however, the county was found to be rich in other minerals, and mines grew in number and size. No longer independent operators, miners were employees who worked long hours at a strenuous and dangerous job for sometimes very low wages.

Chestnut Flats Mine was for many years a prolific producer of several minerals – mica, feldspar, and quartz; they are each part, geologist Alex Glover says, of a rock named Leucogranodioriticmetatonalite. Locals are more likely to call it spar, Pegmatite, or Alaskite. Quartz for the glass of the reflecting telescope at Mount Palomar, CA, came from the Chestnut Flats Mine.

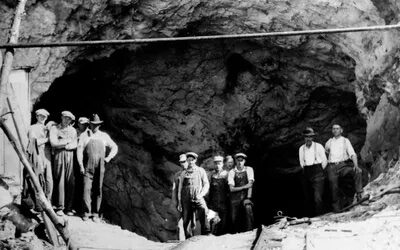

Mining continued to be a family tradition; 3 of the men listed here were father and sons, while two others were uncle and nephew. Standing in the mouth of Chestnut Flats Mine, about 1932, are some of the men who worked there. From left to right: Ed Turbyfill, Arnold Blackburn, Claude Pitman, Jeff Willis, Merritt Sparks, John Duncan, Newland Sparks, Landon Pitman, Walter Buchanan, Ike Grindstaff, Roe Duncan, and Bob Duncan.

Many men who have had haircuts in Spruce Pine have seen this photo, greatly enlarged and framed, on the wall of their barber shop. The photo was displayed first by Terry Buchanan and then by Kenneth Ellis, who donated it to MCHS.

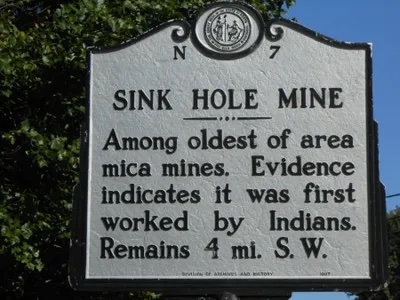

Sink Hole Mine

The Sink Hole Mine in Mitchell County was one of numerous mines in western North Carolina that originally were worked by American Indians before the arrival of white settlers. It therefore was predominantly used for mining mica. Commercial mica production began in 1867 and continued on a mass scale until the 1960s, when the development of solid state electronics led to a decrease in the need for sheet mica. The remains of the Sink Hole Mine are still evident, about four miles southeast of Bakersville.

Mica is composed of a group of aluminum silicates is common in the Blue Ridge Mountains and western Piedmont. Since the 1870s, North Carolina mines have produced the majority of mica in the United States. Sheet mica initially was used as a form of window glass, and then as an insulator for electrical equipment. Additionally, in the early 1900s, scrap mica became a popular product as a friction-causing agent.

There is evidence of mining for a variety of minerals in North Carolina far before the development of modern mining. Although information about earlier miners is lacking, it is believed that mining began prior to 1500. Modern mining in Mitchell County, specifically, was developed in the trenches and mining pits already dug by Indians. Prospectors in western North Carolina from the 1860s expanded upon older mines and developed a formidable industry.

Senator Thomas L. Clingman established the location for the modern Sink Hole Mine, having been hired by a New York mica dealer to investigate the accessibility of the mineral. As word of successful mining spread, mica operations were set up in Avery, Buncombe, Haywood, Jackson, Yancey and Macon Counties. The mining of mica in North Carolina became hugely successful, eventually making the state the dominant source of mica in the nation.

Location: NC 226 at SR 1191 (Mine Creek Road) northwest of Ledger